Spindleberries

A classic short story by John Galsworthy

Illustrated by Jef Franssen

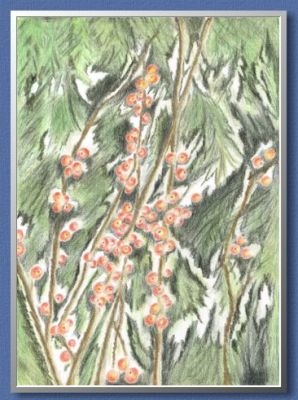

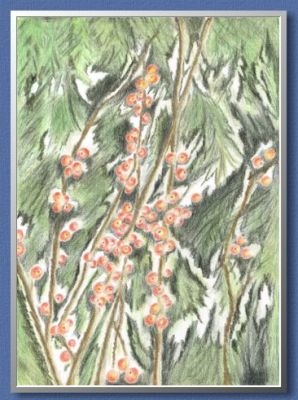

The celebrated painter Scudamore--whose studies of Nature had been hung on the line for so many years that he had forgotten the days when, not yet in the Scudamore manner, they depended from the sky--stood where his cousin had left him so abruptly. His lips, between comely grey moustache and comely pointed beard, wore a mortified smile, and he gazed rather dazedly at the spindleberries fallen on to the flagged courtyard from the branch she had brought to show him. Why had she thrown up her head as if he had struck her, and whisked round so that those dull-pink berries quivered and lost their rain-drops, and four had fallen? He had but said: "Charming! I'd like to use them!" And she had answered: "God!" and rushed away. Alicia really was crazed; who would have thought that once she had been so adorable? He stooped and picked up the four berries--a beautiful colour, that dull pink! And from below the coatings of success and the Scudamore manner a little thrill came up; the stir of emotional vision. Paint! What good! How express? He went across to the low wall which divided the courtyard of his expensively restored and beautiful old house from the first flood of the River Arun wandering silvery in pale winter sunlight. Yes, indeed! How express Nature, its translucence and mysterious unities, its mood never the same from hour to hour! Those brown-tufted rushes over there against the gold grey of light and water--those restless hovering white gulls! A kind of disgust at his own celebrated manner welled up within him -- the disgust expressed in Alicia's "God!" Beauty! What use -- how express it! Had she been thinking the same thing?

He looked at the four pink berries glistening on the grey stone of the wall, and memory stirred. What a lovely girl she had been with her grey-green eyes, shining under long lashes, the rose-petal colour in her cheeks and the too-fine dark hair--now so very grey--always blowing a little wild. An enchanting, enthusiastic creature! He remembered, as if it had been but last week, that day when they started from Arundel station by the road to Burpham, when he was twenty-nine and she twenty-five, both of them painters and neither of them famed--a day of showers and sunlight in the middle of March, and Nature preparing for full Spring! How they had chattered at first; and when their arms touched, how he had thrilled, and the colour had deepened in her wet cheeks; and then, gradually, they had grown silent; a wonderful walk, which seemed leading so surely to a more wonderful end. They had wandered round through the village and down, past the chalk-pit and Jacob's ladder, onto the field path and so to the river-bank. And he had taken her ever so gently round the waist, still silent, waiting for that moment when his heart would leap out of him in words and hers--he was sure--would leap to meet it. The path entered a thicket of blackthorn, with a few primroses close to the little river running full and gentle. The last drops of a shower were falling, but the sun had burst through, and the sky above the thicket was cleared to the blue of speedwell flowers. Suddenly she had stopped and cried: "Look, Dick! Oh, look! It's heaven!" A high bush of blackthorn was lifted there, starry white against the blue and that bright cloud. It seemed to sing, it was so lovely; the whole of Spring was in it. But the sight of her ecstatic face had broken down all his restraint; and tightening his arm round her, he had kissed her lips. He remembered still the expression of her face, like a child's startled out of sleep. She had gone rigid, gasped, started away from him; quivered and gulped, and broken suddenly into sobs. Then, slipping from his arm, she had fled. He had stood at first, amazed and hurt, utterly bewildered; then, recovering a little, had hunted for her full half an hour before at last he found her sitting on wet grass, with a stony look on her face. He had said nothing, and she nothing, except to murmur: "Let's go on; we shall miss our train!" And all the rest of that day and the day after, until they parted, he had suffered from the feeling of having tumbled down off some high perch in her estimation. He had not liked it at all; it had made him very angry. Never from that day to this had he thought of it as anything but a piece of wanton prudery. Had it--had it been something else?

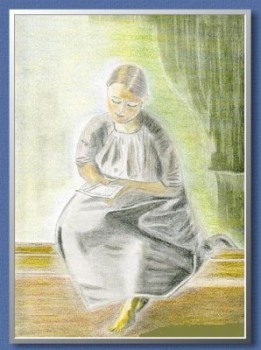

He looked at the four pink berries, and, as if they had uncanny power to turn the wheel of memory, he saw another vision of his cousin five years later. He was married by then, and already hung on the line. With his wife he had gone down to Alicia's country cottage. A summer night, just dark and very warm. After many exhortations she had brought into the little drawing-room her last finished picture. He could see her now placing it where the light fell, her tall slight form already rather sharp and meagre, as the figures of some women grow at thirty, if they are not married; the nervous, fluttering look on her charming face, as though she could hardly bear this inspection; the way she raised her shoulder just a little as if to ward off an expected blow of condemnation. No need! It had been a beautiful thing, a quite surprisingly beautiful study of night. He remembered with what a really jealous ache he had gazed at it--a better thing than he had ever done himself. And, frankly, he had said so. Her eyes had shone with pleasure.

"Do you really like it? I tried so hard!"

"The day you show that, my dear," he had said, "your name's made!" She had clasped her hands and simply sighed: "Oh, Dick!" He had felt quite happy in her happiness, and presently the three of them had taken their chairs out, beyond the curtains, on to the dark verandah, had talked a little, then somehow fallen silent. A wonderful warm, black, grape-bloom night, exquisitely gracious and inviting; the stars very high and white, the flowers glimmering in the garden-beds, and against the deep, dark blue, roses hanging, unearthly, stained with beauty. There was a scent of honeysuckle, he remembered, and many moths came fluttering by towards the tall narrow chink of light between the curtains. Alicia had sat leaning forward, elbows on knees, ears buried in her hands. Probably they were silent because she sat like that. Once he heard her whisper to herself: "Lovely, lovely! Oh, God! How lovely!" His wife, feeling the dew, had gone in, and he had followed; Alicia had not seemed to notice. But when she too came in, her eyes were glistening with tears. She said something about bed in a queer voice; they had taken candles and gone up. Next morning, going to her little studio to give her advice about that picture, he had been literally horrified to see it streaked with lines of Chinese white--Alicia, standing before it, was dashing her brush in broad smears across and across. She heard him and turned round. There was a hard red spot in either cheek, and she said in a quivering voice: "It was blasphemy. That's all!" And turning her back on him, she had gone on smearing it with Chinese white. Without a word, he had turned tail in simple disgust. Indeed, so deep had been his vexation at that wanton destruction of the best thing she had ever done, or was ever likely to do, that he had avoided her for years. He had always had a horror of eccentricity. To have planted her foot firmly on the ladder of fame and then deliberately kicked it away; to have wantonly foregone this chance of making money--for she had but a mere pittance! It had seemed to him really too exasperating, a thing only to be explained by tapping one's forehead. Every now and then he still heard of her, living down there, spending her days out in the woods and fields, and sometimes even her nights, they said, and steadily growing poorer and thinner and more eccentric; becoming, in short, impossibly difficult, as only Englishwomen can. People would speak of her as "such a dear," and talk of her charm, but always with that shrug which is hard to bear when applied to one's relations. What she did with the productions of her brush he never inquired, too disillusioned by that experience. Poor Alicia!

The pink berries glowed on the grey stone, and he had yet another memory. A family occasion when Uncle Martin Scudamore departed this life, and they all went up to bury him and hear his Will. The old chap, whom they had looked on as a bit of a disgrace, money-grubbing up in the little grey Yorkshire town which owed its rise to his factory, was expected to make amends by his death, for he had never married--too sunk in Industry, apparently, to have the time. By tacit agreement, his nephews and nieces had selected the Inn at Bolton Abbey, nearest beauty spot, for their stay. They had driven six miles to the funeral in three carriages. Alicia had gone with him and his brother, the solicitor. In her plain black clothes she looked quite charming, in spite of the silver threads already thick in her fine dark hair, loosened by the moor wind. She had talked of painting to him with all her old enthusiasm, and her eyes had seemed to linger on his face as if she still had a little weakness for him. He had quite enjoyed that drive. They had come rather abruptly on the small grimy town clinging to the river-banks, with old Martin's long yellow-brick house dominating it, about two hundred yards above the mills. Suddenly under the rug he felt Alicia's hand seize his with a sort of desperation, for all the world as if she were clinging to something to support her. Indeed, he was sure she did not know it was his hand she squeezed. The cobbled streets, the muddy-looking water, the dingy, staring factories, the yellow staring house, the little dark-clothed, dreadfully plain work-people, all turned out to do a last honour to their creator; the hideous new grey church, the dismal service, the brand-new tombstones--and all of a glorious autumn day! It was inexpressibly sordid--too ugly for words! Afterwards the Will was read to them, seated decorously on bright mahogany chairs in the yellow mansion; a very satisfactory Will, distributing in perfectly adjusted portions, to his own kinsfolk and nobody else, a very considerable wealth. Scudamore had listened to it dreamily, with his eyes fixed on an oily picture, thinking: "My God! What a thing!" and longing to be back in the carriage smoking a cigar to take the reek of black clothes, and sherry--sherry!--out of his nostrils. He happened to look at Alicia. Her eyes were closed; her lips, always sweet-looking, quivered amusedly. And at that very moment the Will came to her name. He saw those eyes open wide, and marked a beautiful pink flush, quite like that of old days, come into her thin cheeks. "Splendid!" he had thought; "it's really jolly for her. I _am_ glad. Now she won't have to pinch. Splendid!" He shared with her to the full the surprised relief showing in her still beautiful face.

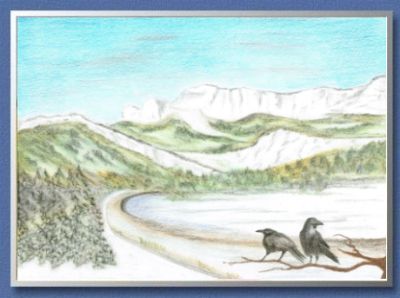

All the way home in the carriage he felt at least as happy over her good fortune as over his own, which had been substantial. He took her hand under the rug and squeezed it, and she answered with a long, gentle pressure, quite unlike the clutch when they were driving in. That same evening he strolled out to where the river curved below the Abbey. The sun had not quite set, and its last smoky radiance slanted into the burnished autumn woods. Some white-faced Herefords were grazing in lush grass, the river rippled and gleamed, all over golden scales. About that scene was the magic which has so often startled the hearts of painters, the wistful gold--the enchantment of a dream. For some minutes he had gazed with delight which had in it a sort of despair. A little crisp rustle ran along the bushes; the leaves fluttered, then hung quite still. And he heard a voice--Alicia's--speaking. "My lovely, lovely world!" And moving forward a step, he saw her standing on the river-bank, braced against the trunk of a birch-tree, her head thrown back, and her arms stretched wide apart as though to clasp the lovely world she had apostrophised. To have gone up to her would have been like breaking up a lovers' interview, and he turned round instead and went away.

A week later he heard from his brother that Alicia had refused her legacy. "I don't want it," her letter had said simply, "I couldn't bear to take it. Give it to those poor people who live in that awful place." Really eccentricity could go no further! They decided to go down and see her. Such mad neglect of her own good must not be permitted without some effort to prevent it. They found her very thin, and charming; humble, but quite obstinate in her refusal. "Oh! I couldn't, really! I should be so unhappy. Those poor little stunted people who made it all for him! That little, awful town! I simply couldn't be reminded. Don't talk about it, please. I'm quite all right as I am." They had threatened her with lurid pictures of the workhouse and a destitute old age. To no purpose, she would not take the money. She had been forty when she refused that aid from heaven--forty, and already past any hope of marriage. For though Scudamore had never known for certain that she had ever wished or hoped for marriage, he had his theory--that all her eccentricity came from wasted sexual instinct. This last folly had seemed to him monstrous enough to be pathetic, and he no longer avoided her. Indeed, he would often walk over to tea in her little hermitage. With Uncle Martin's money he had bought and restored the beautiful old house over the River Arun, and was now only five miles from Alicia's across country. She too would come tramping over at all hours, floating in with wild flowers or ferns, which she would put into water the moment she arrived. She had ceased to wear hats, and had by now a very doubtful reputation for sanity about the countryside. This was the period when Watts was on every painter's tongue, and he seldom saw Alicia without a disputation concerning that famous symbolist. Personally, he had no use for Watts, resenting his faulty drawing and crude allegories, but Alicia always maintained with her extravagant fervour that he was great because he tried to paint the soul of things. She especially loved a painting called "Iris"--a female symbol of the rainbow, which indeed in its floating eccentricity had a certain resemblance to herself. "Of course he failed," she would say; "he tried for the impossible and went on trying all his life. Oh! I can't bear your rules, and catchwords, Dick; what's the good of them! Beauty's too big, too deep!" Poor Alicia! She was sometimes very wearing.

He never knew quite how it came about that she went abroad with them to Dauphine in the autumn of 1904--a rather disastrous business--never again would he take anyone travelling who did not know how to come in out of the cold. It was a painter's country, and he had hired a little _chateau_ in front of the Glandaz mountain--himself, his wife, their eldest girl, and Alicia. The adaptation of his famous manner to that strange scenery, its browns and French greys and filmy blues, so preoccupied him that he had scant time for becoming intimate with these hills and valleys. From the little gravelled terrace in front of the annex, out of which he had made a studio, there was an absorbing view over the pan-tiled old town of Die. It glistened below in the early or late sunlight, flat-roofed and of pinkish-yellow, with the dim, blue River Drome circling one side, and cut, dark cypress-trees dotting the vineyarded slopes. And he painted it continually. What Alicia did with herself they none of them very much knew, except that she would come in and talk ecstatically of things and beasts and people she had seen. One favourite haunt of hers they did visit, a ruined monastery high up in the amphitheatre of the Glandaz mountain. They had their lunch up there, a very charming and remote spot, where the watercourses and ponds and chapel of the old monks were still visible, though converted by the farmer to his use. Alicia left them abruptly in the middle of their praises, and they had not seen her again till they found her at home when they got back. It was almost as if she had resented laudation of her favourite haunt. She had brought in with her a great bunch of golden berries, of which none of them knew the name; berries almost as beautiful as these spindleberries glowing on the stone of the wall. And a fourth memory of Alicia came.

Christmas Eve, a sparkling frost, and every tree round the little _chateau_ rimed so that they shone in the starlight, as though dowered with cherry blossoms. Never were more stars in clear black sky above the whitened earth. Down in the little town a few faint points of yellow light twinkled in the mountain wind, keen as a razor's edge. A fantastically lovely night--quite "Japanese," but cruelly cold. Five minutes on the terrace had been enough for all of them except Alicia. She--unaccountable, crazy creature--would not come in. Twice he had gone out to her, with commands, entreaties, and extra wraps; the third time he could not find her, she had deliberately avoided his onslaught and slid off somewhere to keep this mad vigil by frozen starlight. When at last she did come in she reeled as if drunk. They tried to make her really drunk, to put warmth back into her. No good! In two days she was down with double pneumonia; it was two months before she was up again--a very shadow of herself. There had never been much health in her since then. She floated like a ghost through life, a crazy ghost, who still would steal away, goodness knew where, and come in with a flush in her withered cheeks, and her grey hair wild blown, carrying her spoil--some flower, some leaf, some tiny bird, or little soft rabbit. She never painted now, never even talked of it. They had made her give up her cottage and come to live with them, literally afraid that she would starve herself to death in her forgetfulness of everything. These spindleberries even! Why, probably she had been right up this morning to that sunny chalk-pit in the lew of the Downs to get them, seven miles there and back, when you wouldn't think she could walk seven hundred yards, and as likely as not had lain there on the dewy grass, looking up at the sky, as he had come on her sometimes. Poor Alicia! And once he had been within an ace of marrying her! A life spoiled! By what, if not by love of beauty! But who would have ever thought that the intangible could wreck a woman, deprive her of love, marriage, motherhood, of fame, of wealth, of health! And yet--by George!--it had!

Scudamore flipped the four pink berries off the wall. The radiance and the meandering milky waters; that swan against the brown tufted rushes; those far, filmy Downs--there was beauty! _Beauty!_ But, damn it all--moderation! Moderation! And, turning his back on that prospect, which he had painted so many times, in his celebrated manner, he went in, and up the expensively restored staircase to his studio. It had great windows on three sides, and perfect means for regulating light. Unfinished studies melted into walls so subdued that they looked like atmosphere. There were no completed pictures--they sold too fast. As he walked over to his easel, his eye was caught by a spray of colour--the branch of spindleberries set in water, ready for him to use, just where the pale sunlight fell, so that their delicate colour might glow and the few tiny drops of moisture still clinging to them shine. For a second he saw Alicia herself as she must have looked, setting them there, her transparent hands hovering, her eyes shining, that grey hair of hers all fine and loose. The vision vanished! But what had made her bring them after that horrified "God!" when he spoke of using them? Was it her way of saying: "Forgive me for being rude!" Really she was pathetic, that poor devotee! The spindleberries glowed in their silver-lustre jug, sprayed up against the sunlight. They looked triumphant--as well they might, who stood for that which had ruined--or, was it, saved?--a life! Alicia! She had made a pretty mess of it, and yet who knew what secret raptures she had felt with her subtle lover, Beauty, by starlight and sunlight and moonlight, in the fields and woods, on the hilltops, and by riverside! Flowers, and the flight of birds, and the ripple of the wind, and all the shifting play of light and colour which made a man despair when he wanted to use them; she had taken them, hugged them to her with no afterthought, and been happy! Who could say that she had missed the prize of life? Who could say it?... Spindleberries! A bunch of spindleberries to set such doubts astir in him! Why, what was beauty but just the extra value which certain forms and colours, blended, gave to things--just the extra value in the human market! Nothing else on earth, nothing! And the spindleberries glowed against the sunlight, delicate, remote!

Taking his palette, he mixed crimson lake, white, and ultramarine. What was that? Who sighed, away out there behind him? Nothing!

"Damn it all!" he thought; "this is childish. This is as bad as Alicia!" And he set to work to paint in his celebrated manner--spindleberries.

Afterword

by Brigitte Franssen

When I read this story I was transported back to my childhood days. As a child I was fortunate enough to have a bookshop not far from my parent's house, whose enthusiastic and free-spirited owner supplied me with stories and books, very much like this one, all the time.

I devoured the books as they transported me to a world where I felt at home and safe. I was too young to realise that this world is much more than just a fantasy. Just as John Galsworthy describes in Spindleberries there is a world deep under the surface of our daily lives, filled with rapture, heavenly bliss and divine inspiration. Whoever baths in its waters feels special, deeply loved, well protected and completely connected while at the same time experiencing an intimacy that is hard to describe.

John Galsworthy with this story 'Spindleberries' reminded me of the existence of this world. He gave me the assurance that I am not the only one who is aware of it, nor the only one who wants nothing more than to dwell there; in its beauty, in Beauty.

He, as the great writer he was, must have had his own struggles with the beauty of the world, of a scene, the beautiful drama of its consequences and the sometimes-limited power and reach of words.

We all suffer one way or another. But it wasn't until after I read 'Spindleberries' that I knew what it is I am suffering from while I try to fit in and live in a world of steel. It is an incurable disease of the heart. They call it homesickness.

Beauty: the purpose of life?Read more in the Secret File 'Creation' >>